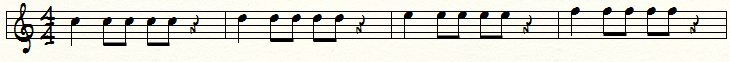

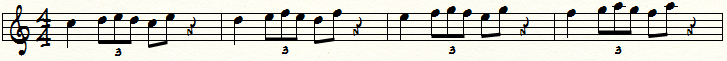

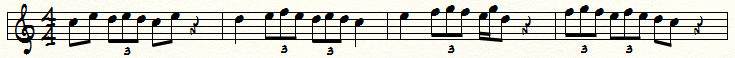

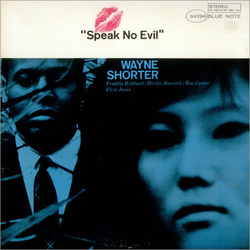

One of the best and fastest ways to improve your improvising is to transcribe solos of the great jazz masters. There are lots of books published which contain volumes of solos but if you truly want to cop someone else's licks, you've got to get your hands dirty and learn 'em off the record. Trust me, I own a bunch of solo books and have collected reams of transcriptions over the years but the licks and phrases that have stayed with me are the ones I took down myself the old-fashioned way. There's no secret here - you must listen, listen, listen and when you are tired of listening, take a break and then come back and listen some more. Memorize, by ear, every lick and phrase and here's the key - be able to sing, note for note, the solo you are attempting to transcribe. The process of actually writing the solo down (if you choose to do so) will go so much faster if you've memorized it first. And after all, isn't that the point of transcribing? To internalize the music of someone you'd like to emulate? Bird took all of Lester Young's recordings into the woodshed and copped 'em all. He didn't write 'em down, he just memorized them all and digested the very essence of Pres. Many students are overwhelmed by the task and don't know where to begin. It's easy: choose a recording you love to listen to. It's really that simple. Don't get wrapped up in the technique or the chords or anything else but the love of the music and your desire to learn it. Choose one track off the recording you love and choose one solo from that track. Listen critically. Listen over and over. Sing along with the solo. Try to sing the inflections. Sing the dynamics. Memorize the solo and be able to sing the solo before trying to play it on your instrument. Please believe me that you will learn the solo SO much faster if you can sing it first. Once you have it memorized, try to play along with it. This may take several attempts and it's perfectly fine to start and stop along the way. I usually will focus on one measure at a time and I'll repeat playing that measure over and over until I get it and then I'll start at the beginning once more and play up until the point where I add another measure. Is it slow going? Yes. Is it challenging? Yes. Is it worth it? Absolutely. As Ellis Marsalis once told me when I was complaining to him about how tough NYC and the jazz scene was: "if it were easy, everyone would do it." Mouth shut and message received. Nothing worth having is going to come easy so if you want to solo like Wayne Shorter, you'd better be willing to put in the time because I guarantee you Wayne did. Here's a copy of the transcription I did of Wayne's solo on Speak No Evil. Enjoy and happy transcribing.

| speaknoevil_waynesolobb.pdf |